The AAPI Community’s Ongoing Struggle with the ‘Model Minority’ Myth

Imagine being celebrated as a “model” citizen while simultaneously feeling misunderstood, isolated, and invisible. For the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community, the “model minority” label is less of an accolade and more of a cage. One that pits communities against one another and hides diverse stories behind a misleading narrative.

The term “model minority” originated from a 1966 New York Times Magazine article written by William Petersen, which highlighted the “success story” of the Japanese Americans who, despite facing years of racial prejudice and discrimination, were still able to achieve socioeconomic success through hard work and cultural values of discipline, work ethic, and compliance to a social hierarchy. Historically, the article fueled a stereotype that frames Asian Americans as economically “useful” members of American society.

In the nineteenth century, as the U.S. economy prospered postwar, immigrants saw the country as a place of opportunity. Many came as refugees fleeing conflict, professionals seeking economic stability, or students pursuing higher education. With ongoing conflicts in Asia and the 1965 Immigration Act reopening doors to Asian immigration, many Asians made long-term investments in relocating to the U.S., hoping for stability and growth.

While Asian immigrants arrived in the U.S. from diverse backgrounds, the U.S. media intentionally promoted the “model minority” stereotype amid Civil Rights Movement tensions to draw a comparison between Asian and African Americans—two marginalized groups historically excluded from the American majority. By presenting Asian Americans as a “successful minority” and contrasting them with African Americans, the “model minority” stereotype has served to reinforce white supremacy, undermining solidarity among communities of color and diverting attention from systemic inequalities.

The idea of the model minority myth is a fallacy because for a group to be socialized as such, they have to assimilate into the dominant culture and gain proximity to whiteness by all means or have racial stereotypes imposed on them. Model minority and bootstrap theory are rooted in capitalist and individualist trains of thought, white supremacist systems of oppression, and encourage oppressed nationalities to compete for capitalist, white supremacist approval.

Valerie Reynoso, “History of the Model Minority Myth in the US,” 2018

Following World War II, as racial tensions intensified in the U.S. and the white majority perceived Asian Americans as both an economic threat and formidable competition for other marginalized groups, many Asian Americans felt pressured to embody the “model minority” stereotype to secure their livelihoods in a racially biased society. The label became controversial because of its long history of stereotyping the racially and ethnically diverse AAPI community, forcing its members under a single umbrella that expects compliance with a restrictive image, often at the expense of their individuality and unique challenges.

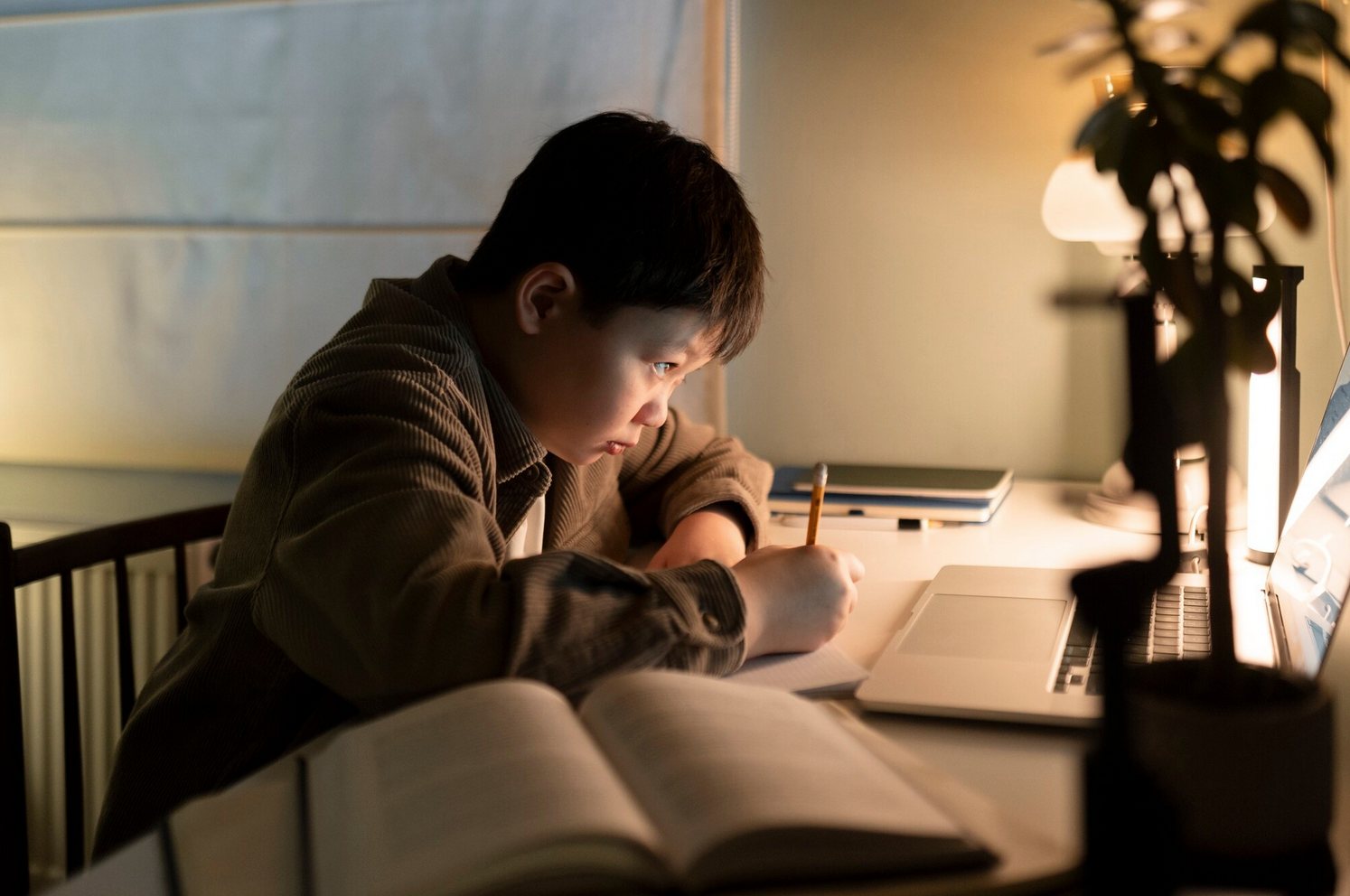

Over time, the term spread collectively to AAPI communities. It remains a tool for comparing AAPIs with other minority groups, reinforcing racial hierarchies. Assuming that all AAPI individuals are academically gifted, hardworking, and economically prosperous creates a false image of universal success, ignoring the real systemic barriers many AAPIs face, such as immigration status, language, and poverty. In education, for example, this stereotype paints AAPIs as naturally skilled in rigorous subjects, particularly math and science. This view reinforced the idea that, as a “model minority,” AAPIs succeed academically and professionally despite personal challenges, suggesting that they are smarter or more capable than other racial groups.

With the assumption that AAPI students should inherently excel, they often feel pressured to meet unrealistic academic standards. For many Asian immigrant families, the decision to move to the U.S. is because of the desire to provide their children with better education and opportunities. Parents often sacrifice their careers, financial stability, and connections in their home countries to give their children a chance at success in the U.S. This immense sacrifice motivates AAPI students to perform well in school, study harder, and achieve academic success, believing these accomplishments are proof that their parents’ sacrifices were worthwhile.

However, while some successful AAPI individuals attribute their achievements to their parents’ sacrifices, others experience intense stress and resentment. The weight of living up to these expectations can be overwhelming, leading to burnout and feelings of inadequacy. Compounding this pressure is the cultural stigma surrounding mental health in many AAPI communities. The expectation to maintain a “perfect” outward appearance often prevents individuals from seeking help, turning the pursuit of success into a burden rather than a choice. This dilemma creates a cycle of silence, where students internalize their emotional struggles and leave their mental health challenges unaddressed, which only deepens the stress they experience.

Another problem that the stereotype overlooked is the ongoing racial discrimination, including AAPI hate. Even in most diverse cities, AAPIs of all backgrounds still feel constantly on edge, fearing verbal harassment, being coughed or spat on, shoved, punched, stabbed, or even killed due to the rise in racial violence. From March 2020 to December 2021, people reported 10,905 hate incidents against AAPIs to Stop AAPI Hate, a national coalition that addresses racism and discrimination targeting AAPIs across the United States.

Even in daily activities, many AAPI individuals have become fraught with fear and anxiety. One story shared on Stand Against Hatred recounts how two Asian students on a late-night bus were targeted with racial slurs, including being called a “noisy Chinese virus,” and threatened with strangulation. One of the students recalled, “I quickly got off and ignored his threats,” emphasizing the distressing impact such encounters have on their sense of safety.

Another story on the platform recounts how a building doorman discriminates against a resident’s mother, refusing to serve her as he does other tenants. The resident described a particularly troubling incident when, in their absence, the doorman yelled at the mother and aggressively punched her package. “We feel unsafe in the building where we’ve owned a unit since September,” the resident shared.

These stories show how, despite the myth of the “model minority,” which falsely suggests that AAPIs are universally successful and accepted, these lived experiences demonstrate how AAPIs continue to be marginalized and subjected to hostility in ways both overt and subtle. The trauma caused by these incidents is compounded by the isolation many feel, as the broader public and even institutions may downplay or ignore the gravity of the situation.

In response to rising violence against AAPI, some leaders have called for increased policing. However, this approach, rooted in legacies of white supremacy and anti-Blackness, has historically failed to address racism effectively in communities of color. Instead of increased policing, advocates and community leaders argue that solutions should focus on addressing the root causes of violence and building lasting support networks for those affected.

This solution could involve investing in mental health services, community-based programs, and educational initiatives that foster understanding and inclusivity. Community members and allies can support local organizations combating hate and promoting racial equity. Organizations like Stop AAPI Hate, Asian Americans Advancing Justice, and Stand Against Hatred offer resources, education, and safe spaces for AAPI individuals to share their experiences and seek help.

Here are a few AAPI foundations or organizations you can also check out and donate to. This list is not extensive, as there are more organizations out there that do incredible work for AAPI populations.

AAPI Equity Alliance, founded by Filipina-American Rachelle Arizmendi, works to improve the lives of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders through civic engagement, capacity building, and policy advocacy.

The National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum (NAPAWF), founded by Yin Ling Leung, empowers AAPI women and girls to have full agency over their lives, families, and communities. NAPAWF drives change by focusing on reproductive rights, economic justice, immigrant rights, and racial justice, working for equal pay, access to healthcare, and freedom from hate and racism for AAPI communities and all people of color.

Chefs Stopping AAPI Hate, founded by chefs Tim Ma and Kevin Tien, is an organization that unites the culinary world to support AAPI and social justice causes. It was created in the Spring of 2021 to raise funds and awareness about the rising violence against Asian Americans in the United States.

Asian & Pacific Islander American Scholars make a difference by mobilizing resources to help students access, complete, and succeed in post-secondary education. The organization develops future leaders who excel in their careers, serve as role models, and contribute to a more vibrant America.

Ending the cycle of violence requires collective action, and the voices of those impacted by hate must be central to shaping solutions. Embracing inclusive policies and actively dismantling stereotypes is crucial in creating a future free from discrimination and fear. Breaking free from the “model minority” myth means acknowledging the complexity and diversity of AAPI experiences and confronting the stereotypes that limit their potential because true equality can only exist when we see every community for who they really are, not through the lens of a stereotype.