How Past Lives Revealed the Walls I Couldn’t See

I had first learned about Past Lives sooner than the rest of the world. It was two years ago in May, when I was hired as part of a loop group, to voice characters and scenes in a story that carried so much resonance with my own. Even the timeline was the same. My family immigrated to Toronto from Tianjin when I was 12. Almost another 12 years later, I made New York my home. For me, the story paralleled so much of my own journey, but the trajectory isn’t uncommon. Unlike Crazy Rich Asians, I would say almost everyone who has loved, let go, and crossed cultures can identify with the themes and feelings that are delicately wrapped inside this third culture story.

A close friend of mine once said that every refugee story is a love story. This story is a love story, without the depth of pain and hardship that comes with refugee territory. So, in a way, yes, it is a story about people with some traces of privilege —- privilege to have come from parents who are artists, with the resources to emigrate; privilege to be pursuing an artistic career — and be awarded a residency — it is a high-achieving, typical New York story, but refreshing in a way that we get to see a life and profile usually reserved and furnished for non-Asian characters on screen.

Refreshing in a way because the Asian American lead presents as someone who dreams big and goes after them with a sense of agency that perhaps her counterparts in Asia don’t have as much. I know this because I was that girl —- embodying and exhibiting more masculine traits through the Eastern lens, but still “quiet” and “sensitive” through the Western lens. A trail-blazer in the East, but very much reserved and withdrawn in the West. The paradox isn’t a true paradox per se, as it mostly exists on the outside — via what others make of what we project, rather than an innate, personality paradox. Nora is who she is, pretty consistently, but strikes as very different only because of cultural valuation and conditioning, upon how the two men perceive her, underlining that the paradox is in perception, not personality.

The story doesn’t spell things out, but hints, in classic East Asian style. For action-craving audiences used to faster paces and higher octane stories, this story seems to only unfold through locations and block years of 12, but nothing really happens. So much exists in the realm of nostalgia and so the cinematography serves to romanticize — normally a style reserved for the French, this kind of impressionism suggests an idealism that is novel for a story with Asian lineage. Privileged in a way because there’s no visible hardship, or the depravities that so often plague and reduce immigrant stories. Privileged because we get to deal with tenderness instead of caricatures.

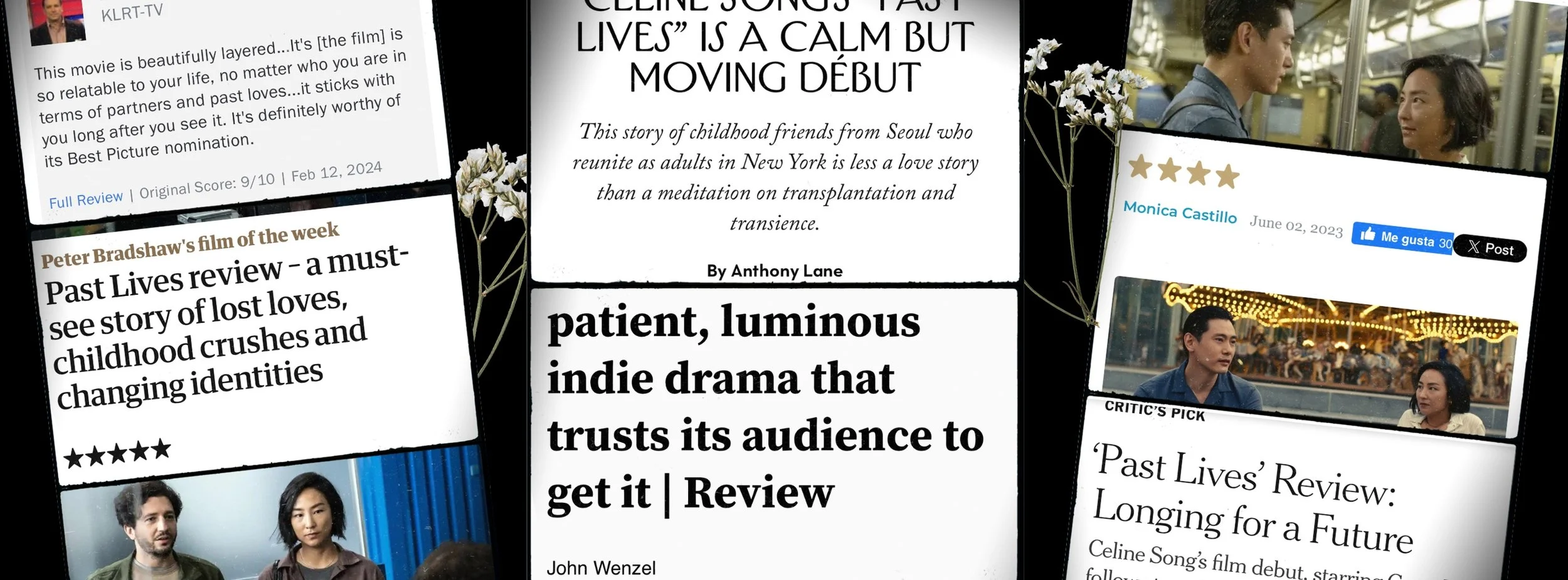

The story is a common one — but perhaps novel to non-Asians, which makes it more important as an Asian American story that needs to be seen and recognized as part of the “American fabric”, instead of it being a “foreign film”, like Parasite would be. Everything Everywhere All At Once does this in a fantastical way, but this story is more subdued in its style, employing romantic cinematography to pay homage to all the cities and places that once were home. And so, the evergreen themes of identity and belonging become the centerpieces. And this is where the commentary — praise and criticism — of the film gets interesting.

The glowing reviews often came from those who grew up never having to question their identity or belonging. The same people are “curious” about culture, and use “multicultural” to describe “third culture”, when they are very distinct experiences and labels — Canada is multicultural; Nora is third culture. You can still grow up in a multicultural environment without ever having left where you were born, so you can in essence, have had a multicultural upbringing without being third culture. But for those who have never dipped their toes in a pool before, the shallow end vs. the deep end won’t register as being different.

However, for those of us who have crossed oceans once or twice or more, the story was “flat”, “hallow”, and many “left the theater bored and baffled.” Most critics of the film have self-identified as Asian American, female, and their responses were recorded in English. Meanwhile, those singing praises praised the film for its “minimalist approach” and understatement — their last names were often non-Asian in their spelling.

We can’t talk about identity without looking at language. In the streets of New York, where so many of us love and live, I hear more languages in a single day than the accumulated months and sometimes even years spent living elsewhere in the world. Language is central to how we identify, self-express, self-determine, and it exposes so much of who we are and what we’re made of. Greta Lee has been quite vocal about how intertwined language is with one’s identity.

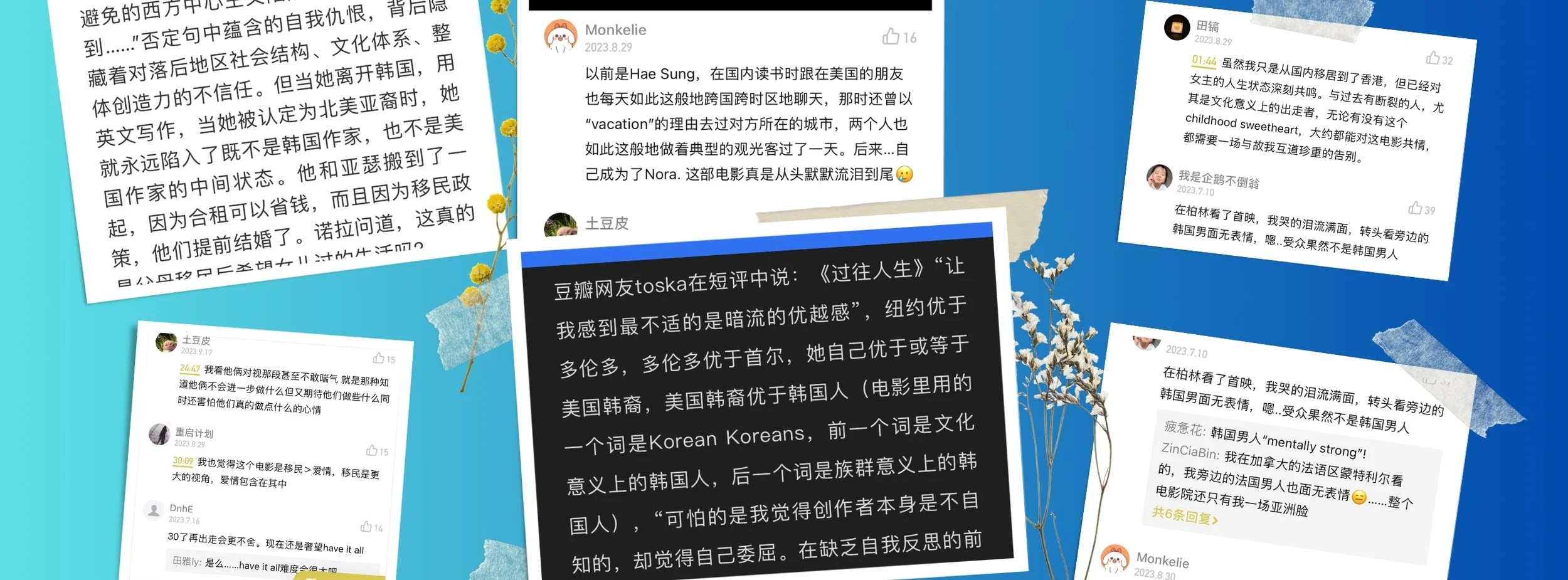

As I was researching the film in Chinese — Mandarin and Cantonese, on sites like zhihu.com, xiaoyuzhoufm.com and douban.com, I read not only the reviews, but also the comments that flooded beneath them. The Chinese analysis dissected the film in a completely different way than its English counterpart. They praised the subtlety of the film, that they cried and held their breaths as the leads walked side by side in silence on screen —- a departure from the vocal American reception who wanted to see more. The Chinese audience relished in the sparsity, in the aching beauty of what remained unsaid, some even identified as being “Hae Sung” at the beginning of cultural crossing —- still chatting with people from home at first, but becoming Nora as time went on — cutting off ties from the land and people that have been left behind. This angle of the Chinese reception is interesting, as it talks about moving within a geographic region — from mainland to HongKong, or from China to Japan. Some cultural crossings aren’t at the same magnitude, but they carry ample nostalgia and struggle as people who have been uprooted. If we have ever searched for a sense of belonging, we will almost for the rest of our lives echo feelings of displacement. You can only know what this feels like if you’ve been uprooted, this almost home like familiarity.

Then, it gets sharper. Because not every person who has ever moved is Third Culture.

One part of Nora’s monologue in particular, ruffled some feathers in a way that identified the ones that may share our skin tone and heritage, but would not be flocking together. So, which part drew the line in the sand that separated those that aren’t of a feather?

It's so crazy to see him be this grown‑up man who has a normal job and a normal life... and he's so Korean. He still lives with his parents, which is really Korean, and he has all these really Korean views on everything, and I just feel really not‑Korean with him. But also, in some way, more Korean? It's so weird. I mean I have Korean friends, but he's like, not Korean‑American, you know? He's a Korean‑Korean.

This paragraph comparing the degrees of one’s Koreaness drove the Mandarin internet into a frenzy. “What’s wrong with a normal job and a normal life? Is she too good for a normal life?”, “What’s wrong with living with your parents?” (Filial piety is engrained sharply in non-American Asians). “Is the director saying that NY>Toronto>Seoul?”, “If the female lead already disowned her culture, why does she look for a sense of belonging? And still a sense of acceptance by the Korean culture?” Truly, this paragraph set off some cultural explosives.

Feathers were ruffled because they sensed cultural hierarchy and superiority — which for me, weren’t there. Switch “Korean” with “Chinese”, and I could have said the very same thing, without qualifying one as better than the other. I think most Third Culture Kids know what this paragraph means. There is no superiority, but there is difference. But clearly, this difference triggers the non-TCK Asian natives very differently.

We can’t talk about TCKs without referencing the scholars who pioneered the term and profile, Pollock and Van Reken. They brought to light the emotional and psychological realities that come with the TCK journey, and categorized 4 ways in which TCKs relate to their surrounding culture.

In essence, TCK’s sense of belonging is rooted in shared experiences and relationships over passport country and places. This is why for Nora, this paragraph comparing Koreaness is simply a neutral reflection of her “in-betweenness”, because every degree of Koreaness offers a different relationship and identity. However, for the non TCK-Asians, this becomes a superiority competition of flags. Hence, this simple paragraph becomes the litmus test for whether someone is third culture Asian or not. The wildly contrasting reception is evidence of the distinct cultural differences between TCK and those who are not, but still "has the face of that culture". TCK knows exactly what every word in this paragraph means and weighs, whereas for Asians who haven’t been uprooted, they see a hierarchy and find this offensive. It’s clear we don’t think alike, but does the hierarchy really exist at the level of the script? Or did the script pull out something encoded within the audiences’ minds themselves, that they so quickly made comparisons and judgments on?

Now you see the invisible differences. We bleed the same, but at different layers, in different places.